Welcome to PICU Doc On Call, A Podcast Dedicated to Current and Aspiring Intensivists.

I’m Pradip Kamat. I’m Dr. Ali Towne, a rising 3rd-year pediatrics resident interested in a neonatology fellowship, and I’m Rahul Damania and we are coming to you from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta – Emory University School of Medicine.

Welcome to our Episode a 5-month-old, ex-28 week female with abdominal distention.

Here’s the case:

A 5-month-old, ex 28 week, female with a past medical history of severe BPD, pulmonary hypertension, home oxygen requirement, and G-tube dependence presents with hypoxemia and increased work of breathing.

The patient has a history of prolonged NICU stay with 8 weeks of intubation. The patient developed worsening respiratory distress requiring increased support and eventual intubation for hypoxemic respiratory failure. Echo showed worsened pulmonary hypertension with severe systolic flattening of the ventricular septum and a markedly elevated TR jet. The patient had poor peripheral perfusion, and upon intubation was started on milrinone and epinephrine. The patient improved, but the patient then developed abdominal distention and increasing FiO2 requirements prompting an abdominal x-ray. X-ray showed diffuse pneumatosis with portal venous gas. The patient was made NPO and antibiotic therapy was initiated.

To summarize key elements from this case, this patient has NEC.

- NEC is not a homogenous disease, but rather a collection of diseases with similar phenotypes.

- Some people split NEC into two categories: Cardiac NEC and Inflammatory NEC.

- Babies who develop cardiac NEC tend to be significantly older than babies who develop inflammatory NEC (about 1 month vs 2 weeks).

- There are three main contributory factors to the development of NEC: gut prematurity, abnormal bacterial colonization, and ischemia-reperfusion injury.

- Many cases result from an ischemic insult to the bowel, resulting in translocation of intra-luminal bacteria into the wall of the bowel, but the etiology and course of NEC can be very variable.

- This translocation can cause sepsis and death; the ischemia of the bowel can result in intestinal perforation and/or necrosis.

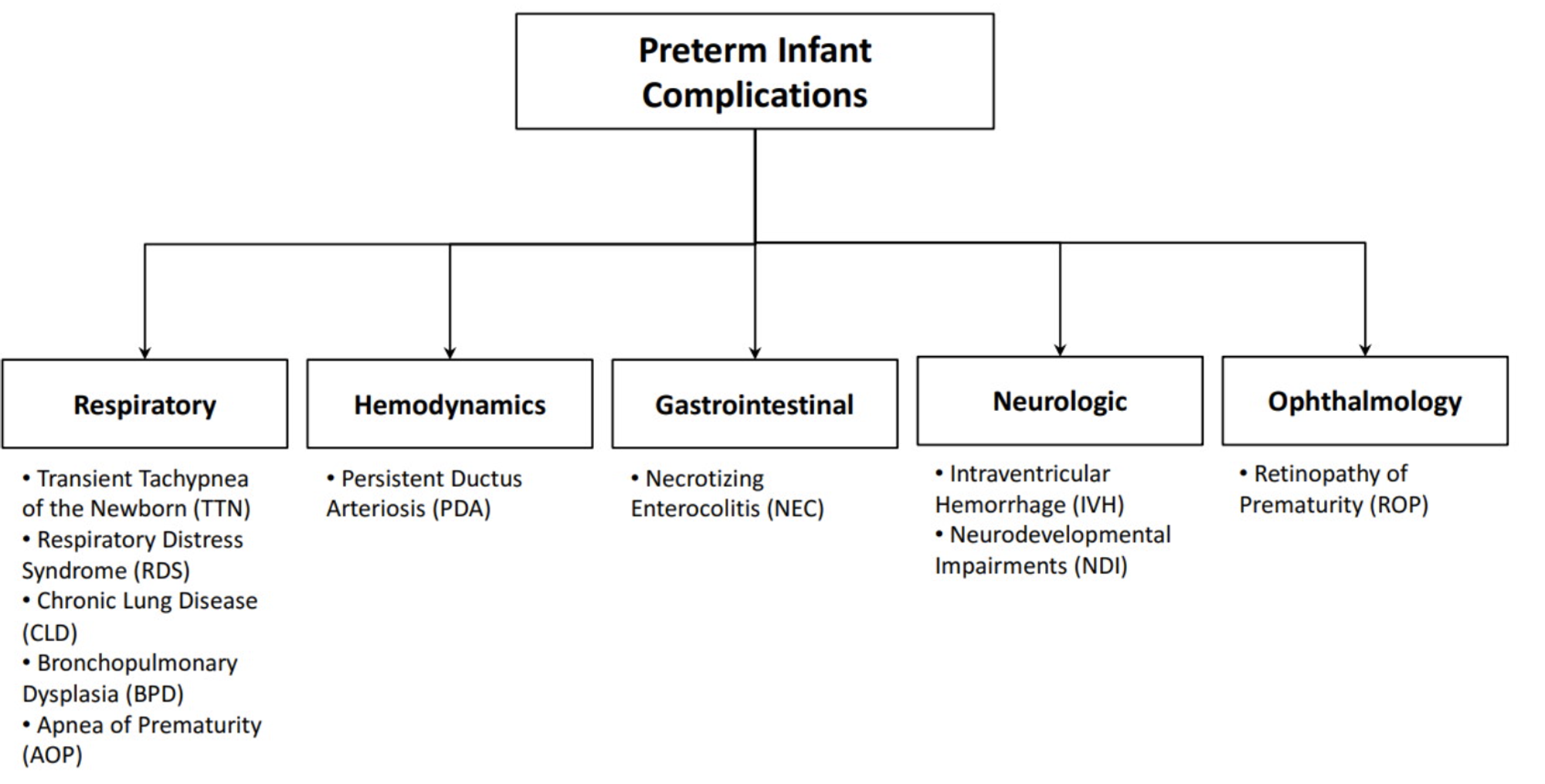

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is one of the most common gastrointestinal emergencies in the newborn infant. It is estimated to occur in 1 to 3 per 1000 live births. More than 90 percent of cases occur in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (BW <1500 g) born at <32 weeks gestation, and the incidence of NEC decreases with increasing gestational age (GA) and BW.

What are key risk factors for the development of NEC?

- Prematurity and Birth Weight

- NEC incidence is inversely proportional to gestational age.

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Puts children at risk for NEC due to (1) decreased stroke volume, and (2) improperly oxygenated blood which reduced oxygen supply to the SMA and decreases intestinal wall perfusion.

- On the repair of the cardiac lesion, patients develop reperfusion injury due to their now improved perfusion to their gut. This reperfusion causes hyper inflammation via neutrophil activation resulting in NEC.

- NEC primarily occurs in healthy, growing, and feeding VLBW preterm infants. It presents with sudden changes in feeding tolerance (increase in gastric residuals) with both nonspecific systemic signs (eg, apnea, respiratory failure, poor feeding, lethargy, or temperature instability) and abdominal signs (eg, abdominal distension, bilious gastric retention and/or vomiting, tenderness, rectal bleeding, and diarrhea). Physical findings may include abdominal wall erythema, crepitus, and induration.

Other than the immediate risk of death, what are some consequences of NEC long-term?

- Higher risk of malnutrition and short gut.

- BPD

- Developmental delay.

What are some areas of current research and development on the topic of NEC?

- Improved biomarkers for early recognition of NEC prior to the development of radiographic findings.

- Preventative measures.

- Immune modulators of NEC development.

- Underdeveloped adaptive immunity of the premature infant may be contributory.

- The normal passive sharing of immune compounds between mother and babies (IgG via the placenta and secretory IgA from breastmilk) is disrupted in premature infants, particularly those that are formula-fed.

- The majority of IgG transfer occurs in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy.

- Several additional cellular and cytokine-based changes may increase the risk of NEC.

A clinical diagnosis of NEC is based on the presence of the characteristic clinical features of abdominal distension, bilious vomiting or gastric aspirate, rectal bleeding (hematochezia), and the abdominal radiographic finding of pneumatosis intestinalis, pneumoperitoneum, or sentinel loops. The definite diagnosis of NEC is made from either surgical or postmortem intestinal specimens that demonstrate the histological findings of inflammation, infarction, and necrosis. However, a pathologic diagnosis is not always possible.

What are some of the currently favored preventative measures used to decrease the risk of NEC?

- Probiotics – research has found that babies with NEC have a different underlying gut microbiome than infants without NEC.

- The underlying suggestion is that “good bacteria” prevent the overgrowth of gram-negative enteric pathogens that may lead to NEC.

- Associated with increased risk in the development of NEC between 30-32 weeks where there is a concomitant change in microbiome colonization.

- Also, some suggestions that “good bacteria” downregulate the inflammatory response in the gut.

- Dosing, type of probiotic, and other details of usage are still yet to be decided on.

- Still not the standard of care in the US.

- Human Milk over Formula – a 1990 study demonstrated that the risk of NEC is 6-10 times greater in formula-fed infants.

- Secretory IgA from breastmilk may be protected as the adaptive immune system develops.

How is NEC managed?

- NEC is typically managed with gut rest (NPO with mIVF), gut decompression (Anderson tube to LIS), and broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage (we use Vanc and Zosyn at CHOA).

- Typically is managed in conjunction with pediatric surgery to evaluate the need for surgical resection.

- Otherwise, management includes supportive care including increased respiratory support as needed and typically TPN given the length of NPO time required.

- Pradip, we talked a great deal about NEC however can you provide some key differentials to consider?

- The differential diagnosis of NEC includes other conditions that cause rectal bleeding, abdominal distension, or intestinal perforation. These include spontaneous intestinal perforation of the newborn, infectious enterocolitis, and other causes of the surgical abdomen. NEC is usually differentiated from these conditions by its characteristic clinical features (healthy, growing, and feeding VLBW preterm infants who present with feeding intolerance and evidence of rectal bleeding) and abdominal radiographic findings (eg, pneumatosis intestinalis).

To Summarize:

- Medical management should be initiated promptly when NEC is suspected and in all infants with proven NEC. It includes the following:

- Supportive care – Supportive care includes bowel rest with discontinuation of enteral intake, gastric decompression with intermittent nasogastric suction, initiation of parenteral nutrition, correction of metabolic, fluid/electrolyte, and hematologic abnormalities, and stabilization of the cardiac and respiratory function.

- Antibiotic therapy – After obtaining appropriate specimens for culture, a course of parenteral antibiotics that cover a broad range of aerobic and anaerobic intestinal bacteria should be started:

- Ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole could be options.

- Vancomycin can be used in areas of high MRSA and can be coupled with Zosyn.

- The clinical status is monitored to see if the patient responds to medical management, or if NEC continues to progress, and to determine if (and when) surgical intervention is required. Monitoring entails serial physical examinations and abdominal radiographs, and ongoing laboratory testing (eg, white cell and platelet count, and serum bicarbonate and glucose measurements).

- Surgical intervention is required either when intestinal perforation occurs or when there is unremitting clinical deterioration despite medical management, which suggests extensive and irreversible necrosis.

This concludes our episode on NEC.Special thanks to Dr. Ali Towne for her deep dive into this topic.

We hope you found value in our short, case-based podcast. We welcome you to share your feedback, subscribe & place a review on our podcast! Please visit our website picudoconcall.org which showcases our episodes as well as our Doc on Call management cards. PICU Doc on Call is co-hosted by myself Dr. Pradip Kamat and Dr. Rahul Damania. . Stay tuned for our next episode! Thank you!

References:

- Klinke M, Wiskemann H, Bay B, et al. Cardiac and Inflammatory Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Newborns Are Not the Same Entity. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:593926.

- Alison Chu M. Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Predictive Markers and Preventive Strategies. NeoReviews. 2013;14.

- Denning TL, Bhatia AM, Kane AF, Patel RM, Denning PW. Pathogenesis of NEC: Role of the innate and adaptive immune response. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(1):15-28.