Welcome to PICU Doc On Call, A Podcast Dedicated to Current and Aspiring Intensivists.

I’m Pradip Kamat and I’m Rahul Damania. We are coming to you from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta – Emory University School of Medicine.

Welcome to our episode, A Three-Year-Old with recent cough and leg weakness.

Here’s the case presented by Rahul.

A 3-year-old previously healthy female presented to the hospital with a 2-week history of productive cough and congestion and the new 1-day onset of bilateral weakness. Today, the mother noticed weakness and inability to stand/walk following after shower as well as her voice becoming hoarse. She also noticed her lying more limp sitting on her lap, unable to sit up fully without her mother supporting her. She had no trouble holding up her head. The mother endorses increased fussiness but is able to be consoled. Decreased p/o intake, last meal was yesterday. About 1-2 weeks prior to this patient also had non-bloody diarrhea that resolved spontaneously after a few days.

UOP normal with 2-3 wet diapers. No difficulty breathing. No history of head trauma or trauma to lower extremities, no erythema/swelling to joints. No pain associated with leg movement. No previous difficulty with walking – developing normally otherwise. No fever, recent travel, H/O sick contact at home (sibling with URI). No allergies, immunization UTD. CMP largely unremarkable. CBC with leukocytosis to 19.72 with L shift and platelets of 647. CRP 0.3, ESR 12.

Afebrile, RR 24/min, HR 130, BP 140/86.

On PE: Patient was coughing, had a hoarse voice heart and lung exam was normal. Normal abdominal exam. No rash

Neurological exam: PERRL, (A+O) X3, 3-4/5 strength at ankles and knees and 5/5 in arms, +UE DTR’s but none at patella or ankles. Has a wide-based ataxic gait and needs to hold on to the wall/furniture to ambulate.

Rahul, to summarize key elements from this case, this patient has:

- A cough with a hoarse voice

- No fever

- Inability to stand/walk (i.e. lower extremity weakness) with no DTRs in patellae or ankle

- Normal mental status

- Diarrhea (non-bloody) preceding neurological weakness

- All of these bring up a concern for Guillain-Barré syndrome-An immune-mediated disease possibly triggered by a recent infection and targeting the peripheral nervous system.

Let’s transition into some history and physical exam components of this case?

- What are key history features in this 3-year-old child

- Acute (B) leg weakness

- Cough with hoarse

- Diarrheal illness

- No fever, no /o rash or trauma

- Pradip, Are there some red-flag symptoms or physical exam components which you could highlight?

- Bilateral lower leg weakness with absent patellar and AJ DTRs

- Normal mental status

- No rash, trauma

- Rahul continues with our case, the patient’s initial labs and imaging were consistent with:

- The CMP, CBC with differential, and blood gas were unremarkable

- ESR = 12, CRP 0.29, pro-cal 0.09(all normal)

- Normal CPK

- Normal Urine analysis

- A lumbar puncture revealed colorless CSF with 4 white cells, 0 reds, Glucose 73 (serum Glucose 90) and protein 94, Gram stain and culture-negative

- MRI of the brain and lumbar spine with and without contrast was completely normal

- Chest radiograph with no infiltrate or atelectasis

- Nerve conduction studies were not performed

Any patient with acute ascending lower extremity flaccid paralysis with CSF showing acellular protein predominance should be considered to have Guillain-Barré syndrome unless proven otherwise. MRI brain spine is necessary to rule out any other etiologies such as brain tumor or spinal pathologies. Features strongly supporting the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome include a progression of onset over several days to less than 4 weeks, symmetrical involvement, painful onset, mild/absent sensory symptoms, cranial nerve involvement, autonomic dysfunction, absence of fever, and recovery 2 to 4 weeks after the onset of peak or plateauing of symptoms.

- Rahul Let’s start with a short multiple-choice question:

- A five-year-old girl with acute ascending bilateral lower limb weakness, normal MRI, CSF with acellular protein predominance would require immediate airway management in case the girl has

- A) A chest radiograph with large atelectasis

- B) A Maximum inspiratory force of -40cm H20

- C) A vital capacity of > 25cc/kg

- D) A strong cough

- Rahul, the correct answer is A.

- Chest radiograph with large atelectasis, which suggests upper airway compromise and weakness of pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles leading to difficulty in the clearing of secretions and airway maintenance and resulting in aspiration. A maximum inspiratory force of less negative than -30cm H20 is a risk for respiratory arrest (i.e. more sub-atmospheric the better), a maximum inspiratory force of -40 is actually good (> 60% predicted). The answer C is wrong because its a vital capacity of < 20mL/kg that puts a patient at risk for respiratory failure. D) A strong cough is not an indication for intubation or suggestive of impending respiratory failure but hoarseness or a weak cough is. Remember trends are more important than a single value. In infants: inability to lift their head when supine, bulbar symptoms, tachypnea, increasing O2 requirement, and use of accessory muscles of respiration implies impending respiratory failure. Remember hypercarbia is a late finding of impending respiratory arrest.

PFT measurement in GB syndrome is remembered as the 20/30/40 rule: A vital capacity < 20ml/kg, a maximum inspiratory pressure less negative than -30cm H2O, or maximum expiratory pressure of ≤ 40cm H2O. Serial measurements are required.

Rahul, what is the pathogenesis of Guillain-Barré Syndrome?

The exact pathogenesis is unknown. An immune trigger such as infection, vaccine, etc affects peripheral nerve components due to molecular mimicry. A gastrointestinal or upper respiratory tract illness within 4 weeks of presentation triggers the onset of Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Possible viral agents include cytomegalovirus (detected in 26%), Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, and human immunodeficiency virus, and bacterial triggers include *Mycoplasma*, *Haemophilus*, and, most commonly, *Campylobacter jejuni*, which accounts for 20% to 30% of US and European cases. Although rare, vaccination (influenza), surgery, trauma, transplant, lymphoma, and systemic lupus erythematosus have also been associated with GBS. Recently GBS after exposure to Zika virus has been described with most patients having a complete recovery.

- As you think about our case, what would be your differential for Guillain-Barré syndrome and neuromuscular weakness in general?

- Encephalopathy. Location cerebral cortex/brainstem. The patient will have altered sensorium, seizures, autonomic dysfunction, upper motor neuron findings, seizures, and movement disorder.

- Cord compression or Transverse myelitis: The location of the lesion is in the spinal cord. unclear etiology, MRI reveals inflammation within the spinal cord. A sensory level is present on the back. There is bilateral, sensory, motor or autonomic spinal cord dysfunction. Bowel bladder dysfunction at presentation or that which persists should lead to questioning of the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Typically rectal tone is maintained in Guillain-Barré syndrome.

- Acute flaccid myelitis: Lesion in anterior horn cell. Sudden onset of arm or leg weakness and loss of muscle tone and reflexes. Preceded by a viral infection such as enterovirus D68. Listeners should be vigilant for vaccine-preventable diseases that are making a come back such as poliomyelitis.

- Botulism: Lesion at NMJ. Presynaptic binding of toxin prevents the release of Acetylcholine. Infants can present with constipation. Descending paralysis with early bulbar findings (weak cry, poor suck, and bilateral ptosis). Can progress to respiratory failure.

- Myasthenia Gravis: Location NMJ. Autoantibodies are directed against postsynaptic AcH receptors leading to destruction. Typically ocular and bulbar muscle weakness is common. Fatigable weakness is a hallmark.

- Organophosphate poisoning: Location NMJ, Inhibits Acetylcholinesterase leading to increased AcH and its action at NMJ. Muscle weakness with miosis, diarrhea, urination, lacrimation, salivation, and bronchorrhea

- Tick paralysis: Location NMJ. Neurotoxin prevents the release of AcH into the NMJ. Symmetric ascending paralysis with areflexia.

- Periodic paralysis. Location: muscle. Episodic muscle weakness triggered by exercise, carbohydrate-rich meal (release of insulin) a genetic mutation affecting Na, K, and Ca ion channels

- Rahul: If you had to work up this patient with Guillain-Barré syndrome, what would be your diagnostic approach?

- MRI brain/spine with and without contrast

- LP with CSF: Typically shows elevated protein and normal cell counts (called albumino-cytological dissociation)is present in only 64% of cases with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Initially may be seen in 50% in the first three days but in 80% of patients after the first week. An elevated CSF cell count > 50 should really cast doubt on the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

- CBC, CMP, CRP, ESR. GI PCR for campylobacter Jejuni (most common infection in the US giving rise to Guillain-Barré syndrome).

- Never conduction studies (NCS): Can help diagnose in difficult cases and help differentiate between axonal and demyelinating subtypes. Nerve conduction studies peak > 2 weeks after onset of weakness. NCS in AIDP reveals features of demyelination such as reduced nerve conduction velocity, prolonged F-wave latency, and prolonged distal motor latency and conduction block. Axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome reveals decreased motor or sensory amplitudes especially with the absence of demyelination features.

- Antibodies: Anti GQ1b antibodies may be detected in 90% of patients with the Miller Fisher variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Anti ganglioside GM1 antibodies may be seen in 50% of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome secondary to Campylobacter jejuni infection. (relatively specific but not sensitive)

Rahul, can you comment on the Guillain-Barré syndrome variants?

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) is considered synonymous with Guillain-Barré syndrome and has the best prognosis. Most prevalent form in Europe and North America.

AMAN (acute axonal motor neuropathy): Has no to minimal sensory symptoms and predominantly presents with progressive flaccid ascending quadriparesis complicated by respiratory failure. (slow recovery and high mortality rate). More prevalent in South East Asia

ASMAN: acute motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy. Both sensory, as well as motor fibers, are involved. It’s a form of axonal GBS and is considered a variant of AMAN.

Miller Fisher Variant: The patient presents with a triad of areflexia, ataxia, and ophthalmoplegia and can progress to AIDP in some cases.

Rahul can you comment on the autonomic dysfunction in Guillain-Barré syndrome

1/2 patients diagnosed with **Guillain-Barré syndrome** will present with autonomic dysfunction such as diarrhea/constipation, bradycardia (15% of patients), followed by hyponatremia, SIADH. Others such as cardiomyopathy, syncope, urinary retention, BP instability syncope, reversible cardiomyopathy, and Horner syndrome are rarely seen. Cranial neuropathies (seen in 60% of patients) in form of bulbar weakness, facial palsy, ophthalmoplegia, and hypoglossal nerve palsy. Bradycardia may be difficult to treat and may require pacing. Patients can have excessive sweating and light-fixed pupils as a part of their autonomic dysfunction. A small percentage of patients can have paresthesias/numbness and pain.

- If our history, physical, and diagnostic investigation led us to Guillain-Barré syndrome as our diagnosis what would be your general management of framework?

- Requires a multidisciplinary collaborative effort between the intensivists, neurologists, apheresis, and the rehabilitation teams.

- Patients (~25%) with risk factors for respiratory failure should be intubated early. This also helps facilitate procedures such as MRI, LP, and placement of a catheter for PLEX.

- Patients with bradycardia, cardiac dysrhythmias, and hemodynamic instability can be difficult to manage. Bradycardia may require pacing. The help of the cardiologist or CICU colleagues is required.

- First-line therapies include IVIG and plasmapheresis. PLEX removes neurotoxic antibodies, complement factors, and other humoral mediators of inflammation. Treatment with PLEX should be initiated in the first 2 weeks of the onset of weakness. Typically five sessions each one administered every other day are performed. IVIG improved symptoms by unknown mechanisms (inhibits Fc mediated activation of the immune cells, binding of antiganglioside antibodies to their neural targets) but may also suppress further autoantibody formation and reduces T-cell and macrophage activation of the immune system. IVIG dose is 2gm/Kg. Steroids have no role in the management of GBS. The use of eculizumab (currently in phase 2 trial) has shown promise but requires RCT.

- Patients require thromboembolism prophylaxis in form of low molecular weight heparin, pain management with opioids, gabapentin, management of urinary retention, as well as constipation. Frequent turning of patients will prevent decubitus ulcers. Aggressive early physical, occupational, and speech therapies are required.

Rahul, what are the Key Objectives and Takeaways?

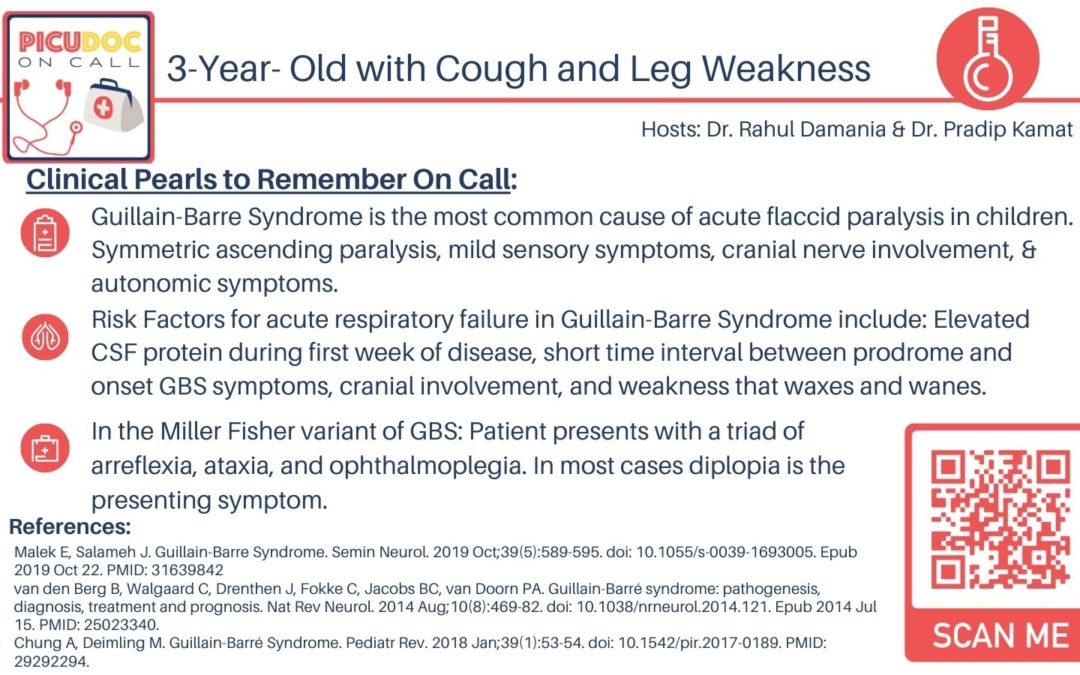

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome is the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis in children. Symmetric ascending paralysis, mild sensory symptoms, cranial nerve involvement, & autonomic symptoms.

- Risk Factors for acute respiratory failure in Guillain-Barre Syndrome include: Elevated CSF protein during the first week of disease, short time interval between prodrome and onset GBS symptoms, cranial involvement, and weakness that waxes and wanes.

- In the Miller Fisher variant of GBS: The patient presents with a triad of areflexia, ataxia, and ophthalmoplegia. In most cases, diplopia is the presenting symptom

- References:

- Malek E, Salameh J. Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2019 Oct;39(5):589-595. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693005. Epub 2019 Oct 22. PMID: 31639842

- van den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, Fokke C, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Guillain-Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014 Aug;10(8):469-82. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.121. Epub 2014 Jul 15. PMID: 25023340.

- Chung A, Deimling M. Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Pediatr Rev. 2018 Jan;39(1):53-54. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0189. PMID: 29292294.

More information can be found

- Fuhrman & Zimmerman – Textbook of Pediatric Critical Care Chapter 68 Acute Neuromuscular Disease And Disorders (Weimer M. et al) page 837-838

This concludes our episode on Guillain-Barre Syndrome. We hope you found value in our short, case-based podcast. We welcome you to share your feedback, subscribe & place a review on our podcast! Please visit our website picudoconcall.org which showcases our episodes as well as our Doc on Call management cards. PICU Doc on Call is hosted by myself Pradip Kamat and my cohost Dr. Rahul Damania. Stay tuned for our next episode! Thank you!