Welcome to PICU Doc On Call, a podcast dedicated to current and aspiring intensivists. My name is Pradip Kamat.

And my name is Rahul Damania, we come to you from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta/Emory University School of Medicine. Today’s episode is dedicated to Noninvasive and Invasive ventilation in children post-hematopoietic cell transplantation.

We are delighted to be joined by Dr. Courtney Rowan, MD, MSCR, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, and the Director of the Pediatric Critical care Fellowship at Indiana University School of Medicine/Riley Children’s Health.

Dr. Rowan’s research interest is in improving the outcomes of immunocompromised children with respiratory failure. She is active in this field of research and has led and participated in multi-centered studies. She is the co-chair of the committee of the hematopoietic cell transplantation subgroup of the Pediatric acute lung injury and sepsis investigators network. In our podcast today we will be asking Dr. Rowan about the findings of her recent study published in the journal-Frontiers in Oncology reporting on the risk factors for noninvasive ventilation failure in children post hematopoietic cell transplant.

She is on twitter @CmRowan.

Patient Case

I will turn it over to Rahul to start with our patient case…

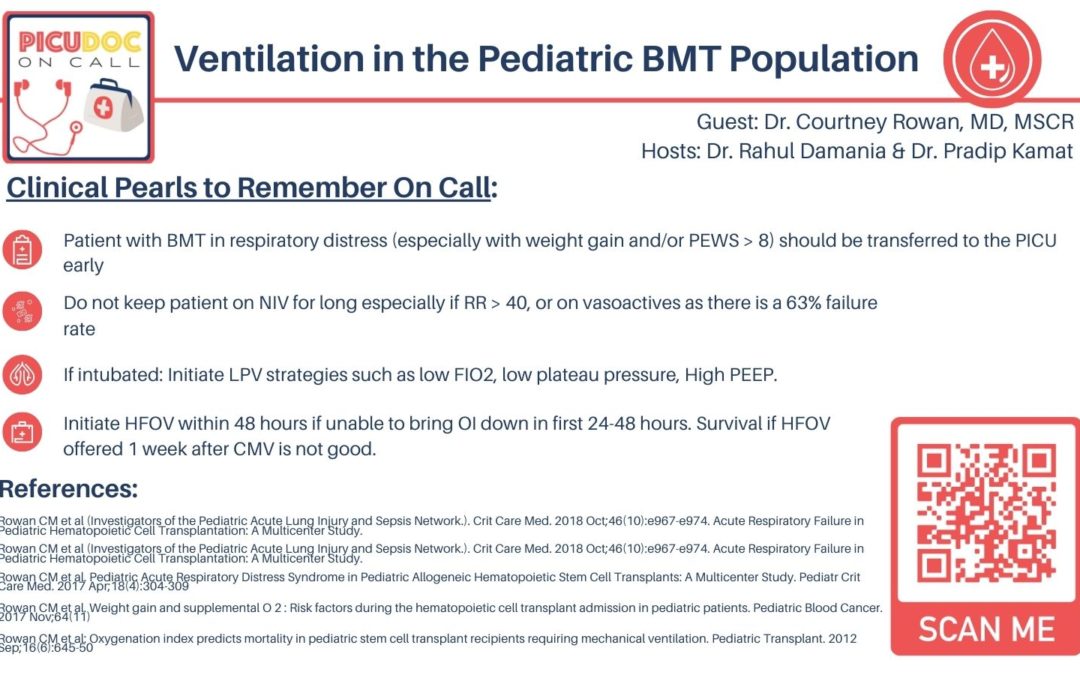

- A 15-year-old female with a history of AML s/p Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation T+15 days presents with tachypnea and a new O2 requirement. She has been on the BMT floor for 48 hrs after being admitted for respiratory distress and fevers. Her blood cultures are negative but she is febrile intermittently. Her CXR shows nonspecific haziness, no focal opacity, and underinflation. Her weight is up 2KG in the last 48 hours. She is found to have increased work of breathing and mild desaturations to 88%. She is placed on HFNC and continued on broad-spectrum antibiotics. A respiratory viral panel and Sars-CoV-2 PCR is sent. Transfer to the Pediatric ICU is initiated.

Episode Dialogue

Dr. Rowan, welcome to our PICU Doc on-call podcast.

Dr. Rowan: Thanks Rahul & Pradip for having me. I am delighted to be here to discuss one of my favorite topics. I have no conflicts of interest but I have funding from the NHLBI.

Today we will be discussing the up-to-date evidence for NIV (HFNC and NIPPV) use in children who have had BMT. Additionally, we will also be discussing the use of invasive MV strategies including HFOV in the pediatric BMT population. To start us off, Dr. Rowan, why is the BMT cohort different from other patients admitted to the PICU?

There is an increase in the # of patients undergoing BMT as indications for BMT are being expanded to different disease processes. The Etiologies for lung disease in BMT patients can be infectious (common organisms as well as opportunistic organisms). They can have lung disease from non-infectious causes and even fluid overload from renal dysfunction/medications given and there is a constant threat of alloreactivity which can manifest as GVHD or engraftment syndrome. 75% of PICU admits of immunocompromised children come from the heme-onc inpatient services. BMT patients have a higher risk to progress to ARDS. Recent reports show the incidence of ARDS in the intubated BMT population reaching upwards of 92%. These patients are also at high risk for MODS and can have a mortality rate close to 60%.

💡 To summarize, the BMT population is a unique ever-growing population that represents a relatively large cohort of immunocompromised children in the PICU with a risk of high mortality. As we have set this basis, we will be focusing the rest of our episode on the need for early recognition and intervention in this special population.

- Dr. Rowan: A common conundrum faced by the PICU team given limited resources and bed availability is when to transfer a patient with BMT to the PICU especially when they start requiring respiratory support on the floor. Are there any risk factors we as PICU physicians need to know which can help us transfer a child from the BMT floor to the PICU in a time-appropriate manner?

Dr. Rowan: This is a great question. We have had a few studies examining this very question. In a paper we published in Pediatr Blood Cancer in 2017, we evaluated 87 allogeneic HCT recipients to investigate the association of clinical risk factors with the development of respiratory failure.

Of the 87 allogeneic HCT recipients, 22 (25%) developed respiratory failure. The group with respiratory failure had a significantly higher percent weight gain increase at multiple time points.

The odds ratio, (OR) for respiratory, failure increased with increasing percentage peak weight gain. We also found that the OR for respiratory failure in patients requiring more than 1 liter supplemental O2 is 25.3 (6.5, 98.7).

We concluded that the percent weight gain and need for supplemental oxygen is highly associated with the development of respiratory failure in pediatric HCT recipients. Additionally, Dr. Algunik et al, have reported (PCCM 2016) that Pediatric Early Warning Score is highly correlated with the need for unplanned PICU transfer in hospitalized oncology and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Additionally, the authors also reported an association between higher scores and PICU mortality. In another study, Dr. Algunik et al (Cancer 2017)reported that PEWS accurately predicted the need for unplanned PICU transfer in pediatric oncology patients in this resource-limited setting, with abnormal results beginning 24 hours before PICU admission and higher scores predicting the severity of illness at the time of PICU admission, need for PICU interventions, and mortality.

Cater et al (PCCM 2018) showed that adding weight gain to PEWs (cutoff of 8) score can increase specificity as well as the AUC to predict children with BMT at risk for clinical deterioration.

💡 Key points from these studies which we can clinically apply — trending of weights and attention to respiratory support and PEWS. Contingency planning and prompt recognition of when to initiate a transfer from floor to PICU is essential in intervening early.

- Dr. Rowan: What are the advantages of early transfer of BMT patients to the PICU?

A controlled transfer with the pediatric patient not in extremis allows for opportunities and time for in-depth multidisciplinary discussion.

This also allocates time for goals of care discussions.

We need to balance this with bed availability, familial stress of transitioning their stay from the floor to the PICU and introduction of a new care team being us in the PICU.

Dr. Rowan: In the case above, our patient was started on non-invasive PPV and antibiotics prior to transfer to the PICU. Could you comment on the ideal interface to provide respiratory support in our patient in this case?

- Little data for BMT pediatric patients for NIV compared to adults. Adult studies show that there is no difference between HFNC and standard O2 (Lemiale CCM 2017) in terms of intubation rate /mortality. Similarly, a large RCT in 776 immunocompromised adults which compared HFNC to standard O2 therapy showed no difference to 28-day mortality, LOS (ICU) stay, patient comfort or dyspnea scores (Azoulay E JAMA 2018).

- As mentioned there is Limited Pediatric data on HFNC use in BMT patients however we can extrapolate that the pediatric BMT population are not merely “tiny adults” and have different respiratory mechanics as well as a physiologic reserve.

- Multiple RCT of NIV vs supplemental O2 (374 organ transplant patients) (Antonelli JAMA 2015) showed no difference in intubation rates or mortality. Frat (Lancet 2016): Compared Adults on HFNC to NIV via supplemental O2 in 82 immunocompromised adults. They concluded that those on supplemental O2 had the highest risk for intubation and worst survival. A study by Squadrone V., et al in Intensive Care Med, published in 2010 Compared early 40 adults with BMT who were placed on CPAP were less likely to go to ICU, less likely to be intubated, and had better survival.

- Pediatric data on NIV is limited however a study by Pancera and colleagues published in 2008 in the journal of Pediatric Heme Onc concluded that the use of BIPAP in the pediatric oncology population was associated with adverse outcomes especially in patients with hemodynamic compromise.

💡 Yes from both the adult and pediatric literature It seems like there is a trend towards worsened outcomes with non-invasive ventilation in a BMT patient with acute respiratory failure.

- Dr. Rowan, we would love to hear more about your research interests specifically related to the pediatric BMT population. How have you addressed the challenge of limited pediatric critical care studies on the Pediatric BMT population?

- As this is a growing population of interest We have created the SIRCH (Study of Intensive Care and Respiratory Support in Children Post HSCT) database to offer collaboration across institutions in efforts to optimize patient care and understand key patient trends. The search database is comprised of 12 centers across the nation. One of our unique students looked at pediatric BMT patients aged 1 month to 21 months with RF. In our population of 222 individuals, we found that patients on NIV had a higher mortality and risk of pARDS (especially at 48 hrs).

- As we have commented on non-invasive PPV, let’s transition to intubation and MV. What are the risk factors for intubation in BMT patients treated with NIV?

- Great question. We developed a study that looked at 153 non intubated patients who were treated with NIV: Risk factors for failure were evaluated:

- RR > 40, Vasoactive use were the biggest risk for developing RF requiring intubation. matched related donor was protective. (Rowan CM, Frontiers in Oncology 2021).

💡 This is a great summary point that answers the question when do these patients need to be considered for intubation:

- Tachypnea

- Vasoactive use

Dr. Rowan, If a BMT patient needs intubation, what does your study using search data inform us of?

- Of the 153 patients who received NIV, 63% progressed to intubation. A small subset of these patients, around 10% of the 97 who were intubated, had a cardiac arrest during intubation. And of those who arrested during intubation, only 18% survived to PICU discharge.

- 24% of patients who arrested peri-intubation had a NiPPV started outside of the PICU. 8% of children who arrested upon intubation had NiPPV started in the PICU.

- Our search database also -used PALICC criteria to define ARDS after these children were intubated. We found that 92% of intubated HSCT patients have ARDS in the first 3-7 days (Rowan PCCM 2017). The majority are diagnosed with PARDS on the day they are intubated.

💡 This high percentage of ARDS in intubated pediatric patients with BMT is close to the incidence in adult studies.

- If we take a step back, what were the characteristics of children who survived with NIPPV?

- Those who were successful with NIV had better PICU survival 90%, however, hospital mortality was 41% when placed on NIV regardless of whether they were successful or failed NIPPV. My personal opinion is that we are pushing NIV too much and too long. Don’t delay intubation. As we see, this may increase the risk for cardiac arrest.

- If we comment on our case further, our patient on HFNC now continues to worsen and upon admission to the PICU is escalated to BIPAP and is initiated on a norepinephrine infusion for vasoplegia and shock. The PICU team decides to intubate. What would be your approach in this high-risk situation?

- Intubation should be a multi-disciplinary approach. This patient in particular is high-risk not only due to her significant past medical history but also the concurrent hemodynamic instability!

- Exactly. As we know, these patients are at high risk for ARDS.

Our strategy, once the patient is intubated, should be surrounding lung-protective ventilation.

These include close attention to:

- Plateau pressures

- Driving pressures

- Higher PEEP

- and lower FiO2

Our goal is to decrease ventilator-induced lung injury. (Rowan PCCM 2018).

- 💡 Totally agree. And for our listeners, please refer to our prior episode on high-risk intubation to review key management principles surrounding the hemodynamically unstable patient.

- This is a great overview, what specific numerical values or trends should we target in our management?

- Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) is the first value. Our studies show that PIP > 31 had an increase in mortality.

- Particular attention to OI should also be a cornerstone of management. In fact, we showed a 13% increase in mortality for every 1 unit increase in OI (Rowan 2012). Patients who had an OI > 18 had upwards to 24% increase in mortality.

- In line with Oxygenation limiting, FiO2 is key. In patients requiring upwards of 60% FIO2 and four times greater odds of mortality, we found that there was heterogeneity amongst centers and some centers did not use a high PEEP-low FIO2 strategy or grid. Centers that were compliant with a high-peep low FIO2 strategy had better survival.

- In terms of ventilation, we need to allow for permissive hypercapnia.

💡 Summary: limit peak pressures, initiate high PEEP early, and limit FiO2.

Dr. Rowan: Our patient now is intubated and has an OI of 28. The patient is starting to have increased peak pressures to 35. She has saturations ~87% with high-mean airway pressures. How would you approach the management in this case?

- At this time it is important to consider HFOV or APRV (Yehya PCCM 2014): If O2 gets better at 24 hrs the child will have a higher likelihood of surviving.

- From our SIRCH database, 85 patients/222 received HFOV (Rowan Resp care 2018). If HFOV started after 48 hrs none of the kids survived. Lower OI at 24hrs after initiation of HFOV was correlated with increased survival. Those who didn’t survive continued with higher OI past 24 hours. We showed no survival in patients who received HFOV after 1 week of conventional mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Rowan, would you mind commenting on the data related to early vs. late oscillator initiation?

- Using the SIRCH database, we identified children with severe pARDS.

- We compared early HFOV (within the first 2 days) vs late HFOV (> 2 days start) compared to CMV. Early HFOV had better survival, whereas late HFOV only 9% survived.

- Adding HFOV after a week of CMV may not offer a survival benefit.

💡 The summary for our listeners here is to consider if HFOV is indicated within 48hrs from CMV to allow for peak survival.

Unfortunately, the patient in the above case died during her stay in the PICU. If we reflect, were there opportunities for us to improve her outcome?

This is a great question and as there are many factors that are patient-specific. Here are some general rules to consider:

- Early transfer to the PICU upon recognition of respiratory failure

- The trend of weights and optimizing diuresis in the setting of fluid overload

- A consideration to intubate early and if oxygenation continues to be poor early use of HFOV

Conclusion

Dr. Rowan, we appreciate your insights on today’s podcasts, as we wrap up, would you mind highlighting your personal clinical pearls related to the critically ill pediatric BMT population?

- Transfer early, allow for early aggressive diuresis, have a multidisciplinary discussion to arrive at a strategize to offer early intubation vs staying on NIV.

- Once intubated use lung-protective strategies: low TV, High PEEP-Low FIO2.

- Transition to HFOV early (< 48 hours) for higher OI. reconsider with the team about offering HFOV after a week of CMV as survival is poor.

This concludes our episode today on Noninvasive and Invasive ventilation in children post-hematopoietic cell transplantation. We hope you found value in this short podcast. We welcome you to share your feedback & place a review on our podcast. PICU Doc on Call is co-hosted by Dr. Pradip Kamat and myself Dr. Rahul Damania. Stay tuned for our next episode! Thank you.