Welcome to PICU Doc On Call, A Podcast Dedicated to Current and Aspiring Intensivists.

I’m Pradip Kamatand I’m Rahul Damania. We are coming to you from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta – Emory University School of Medicine.

Welcome to our Episode of a 19 month old female with bloody stool, petechiae and no urine output

Here’s the case presented by Rahul:

A 19 month old previously healthy female was brought to the pediatric emergency department for blood in her stool. Patient was at daycare the previous day where she developed a low grade fever, congestion and URI symptoms along with non-bloody-non-bilious vomiting and diarrhea. Patient had a rapid COVID test which was negative and was sent home with instructions for oral hydration. That evening, patient began having vomiting/diarrhea which worsened. She was unable to retain anything by mouth and her parents also noted blood in her stool.

Due to this, she was rushed to the Emergency Department. In the ED here, she was hypertensive for age BP of 124/103 mm Hg, febrile, and ill. Specks of blood were noted on the diarrheal stool in the diaper.

On her physical exam she was noted to be pale with petechiae on neck and chest. Her abdomen was soft, ND, with some hyperactive bowel sounds, and no hepatosplenomegaly. The rest of her physical examination was normal.

In the ED, initial labs were significant for WBC 19, Hgb 8.8, and Platelets 34. CMP was significant for BUN of 74mg/dL and Cr of 3.5mg/dL, Na 131 mmol/L, and K of 5.5mmol/L, Ca 8.3mg/dL (corrected for albumin of 2.2g/dL), Phosphorous 8.5 AST 413, and ALT of 227, LDH > 4000. BNP was 142 and troponin negative. She was given 1 dose of CTX 50mg/kg and a 20cc/kg NS bolus. Stool PCR was sent. She was given labetalol for her hypertension, started on maintenance IV fluids and transferred to the PICU for further management.

Rahul to summarize key elements from this case, this patient has:

- We have a 19-month old child with

- Diarrhea and emesis X 2 days

- No urine output for over 24 hours

- Bloody stool

- Petechiae on the neck and chest

- Anemia and thrombocytopenia

All of which bring up a concern for hemolytic uremic syndrome the topic of our discussion today

Let’s transition into some history and physical exam components of this case.

What are the key historical features in this child who presents with above?

- Bloody stool which alludes to an invasive diarrhea

- No urine output and an ill appearing state which points to a systemic inflammatory condition and end organ dysfunction.

Are there some red-flag symptoms or physical exam components which you could highlight?

- Presence of petechiae which are physical exam features of thrombocytopenia

- Her pallor which is a physical exam sign of anemia

- Hypertension which is related to her renal dysfunction

To continue with our case, the patient’s labs were consistent with:

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Elevated BUN and creatinine

- Elevated serum LDH

- The patient did not have hyperkalemia, or acidosis on initial presentation

OK to summarize, we have a 19 month old girl with:

- Anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure. This brings up the concern for Hemolytic uremic syndrome →

Rahul Let’s start with a short multiple choice question:

A 2-year old boy is admitted to the PICU with acute respiratory failure secondary to pneumococcal pneumonia. On day # 3 of admission, the nurse reports the patient appears pale and has petechiae on his chest. The patient also has not had urine output for > 12 hours and appears to be fluid overloaded. Of the following the lab findings would be most consistent with the above clinical findings in the patient?

- A) Elevation of serum haptoglobin

- B) Low serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- C) Negative Direct Coombs test

- D) Peripheral smear showing schistocytes

- The correct answer is D-Peripheral smear showing schistocytes.

Patient in the above case most likely has streptococcus pneumoniae associated hemolytic uremic syndrome commonly called as pneumococcal HUS, an uncommon condition, which accounts for 5% of all cases of HUS in children. A peripheral smear will show the presence of schistocytes (which consists of fragmented, deformed, irregular red blood cells). The schistocytes represent RBCs that are partially destroyed as they traverse through the blood vessels partially occluded by microthrombi. Smear may also show giant platelets due to the rapid platelet turnover from peripheral destruction. Because HUS is an intravascular hemolysis serum haptoglobin should be low. Serum LDH along with indirect bilirubin are typically elevated. The Direct Coombs test detects antibodies that coat RBCs and may allude to this pathology. In pneumococcal HUS where there is antigen-antibody interaction on RBC cell surface, the Direct Coombs test may be positive in 90% of the cases. A direct Coombs test is highly sensitive for pneumococcal HUS, but the degree of specificity is unclear.

A few points which I want to highlight classically on board exams, schistocytes look like helmet cells on blood smear. Also, presence of COOMBs positivity in the setting of hemolysis think about autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA).

- Rahul As you think about our case, what would be your differential?

The following may sometimes be difficult to differentiate from HUS

- Bacterial sepsis (History, clinical presentation with hemodynamic compromise and feature of distributive shock, fever with elevated WBC with neutrophil predominance, multiorgan presentation, source of infection, immunocompromised host etc)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (history of sepsis, drug, toxin eg snake venom, abnormal coagulation etc.)-In HUS the fibrinogen, PT, PTT are normal or slightly elevated and there is no active bleeding.

- Acute hemolysis from any other causes (drugs, toxins, warm-antibody, cold agglutinin disease, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria etc.) -typical history, likely older patients, PNH post-viral in children.

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), acute macrophage activating syndrome (MAS), liver failure, TMA etc (good history, h/o JRA and other features may be helpful).

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (older patient, neurological symptoms)

- The classic triad of hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and renal failure is associated with hemolytic uremic syndrome can be seen on the spectrum of TTP — which adds fever and neurological symptoms to the diagnosis. In the pediatric population, TTP can be seen when children have acquired or congenital absence of ADAMS TS 13. Think of ADAMS TS 13 as a pair of scissors that cuts up vWF, an essential component of primary hemostasis. When you have a deficient or mutated ADAMS TS 13, which is a MMP, you end up having large vWF multimers which deposit in between endothelial cells which creates a consumptive thrombocytopenia and intravascular hemolysis.

- Pradip, do you mind building a framework between typical HUS versus Atypical HUS?

- Typical HUS is seen in patients with STEC diarrhea, or invasive pneumococcal disease, such as pneumonia. The atypical HUS is a term reserved for complement mediated HUS in which there is uncontrolled complement activation using the alternative pathway.

Rahul, before we go into the diagnostic and management framework can you shed some light on the pathogenesis of HUS?

The hemolytic uremic syndrome comes under an umbrella term called Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) syndromes. The clinical features of TMA include microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and organ injury. The pathological features are vascular damage that is manifested by arteriolar and capillary thrombosis with characteristic abnormalities in the endothelium and vessel wall.

Let’s breakdown the three pathogenesis or sub-diagnoses:

- In STEC HUS (accounts for most of the HUS seen in children):

- Enterohemorrhagic E coli expresses adhesin called intimin, allowing the Shiga Toxin to enter the bloodstream.

- Once in the bloodstream the Shiga Toxin binds to globotriaosylceramide (Gb3, also known as CD77 or ceramide trihexoside) on endothelial cells, as well as to renal mesangial cells and epithelial cells.

- After endocytosis, the toxin causes ribosomal inactivation leading to cell death.

- Shiga Toxin is pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic and induces endothelial Von Willebrand factor resulting in thrombosis.

- Multiple E Coli species produce the Shiga toxin but E Coli 0157:H7 is the most common in Europe and North America. S. dysenteriae Type 1 is an important cause of Shiga toxin HUS in other countries. STEC HUS is seen in younger children (3-5 years). Severe disease is seen in those with high white counts on initial presentation, female gender and younger age.

Pradip, what is the second subtype?

- Pneumococcal HUS (accounts for 5% of all HUS seen in children): Neuraminidase produced by the pneumococci cleaves the n-acetyl neuraminic acid from cell surface of platelets, RBC and glomerular cells and exposes the Thomsen Friedenreich (TF) crypt antigen. The TF antigen is typically hidden by the neuraminic acid. Once the TF antigen is exposed, preformed IgM antibodies bind to the TF antigen resulting in a cascade of events leading to hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Finally, let’s talk about atypical HUS.

Atypical HUS or complement mediated HUS accounts for approximately 10% of cases seen in children – what is the pathophysiology of this disease?

- In Atypical or complement mediated HUS the gain or loss of function mutations in complement regulatory protein results in uncontrolled activation of the alternative pathway of complement.

- Unlike the other two pathways of complement activation, the alternative pathway is constitutively active as a result of spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 to C3b.

- In the absence of normal regulation, C3b deposition on tissues may increase markedly, resulting in increased formation of the C5b-9 terminal complement complex (also called the membrane-attack complex) leading to endothelial injury and TMA.

- 30% of patients may not have any mutation in complement genes at presentation. 80% of patients present with a fulminant course (after acute URI or viral gastroenteritis). Low C3 with normal C4 indicates alternative pathway activation. Extra-renal manifestations such as seizures, hemiplegia, diplopia, blindness, coma, cardiac and lung involvement are also seen.

- Rahul: If you had to work up this patient with HUS, what would be your diagnostic approach?

- Before we get into this, lets create a mental model: 1) Show evidence of hemolysis, 2) find a source/cause and 3) determine severity of organ involvement

- Excellently said, Initial tests include CBC with differential, peripheral smear, DIC panel, Direct Coombs test.

- A comprehensive metabolic panel, serum LDH, serum haptoglobin, complement levels (C3 and C4), urinary NGAL.

- Blood culture, stool PCR/culture, respiratory culture from ETT

- Imaging and other diagnostics include: Chest radiograph, echocardiography, and renal ultrasound. Daily weights are highly recommended for the patient.

- Disease severity can be gauged by acidosis, hyperkalemia, LDH level and platelet count. Recovery of platelet count followed by decrease in LDH suggests improvement of hemolysis. Persistent hyperkalemia/acidosis suggests an urgent need for dialysis along with decreased UOP, fluid overload and weight gain.

- Other labs that may be needed on a case by case basis include ADAMTS-13 (needed for diagnosis of TTP) or complement 3 glomerulopathy (C3G) functional panel (Includes Complement Antibody Panel, Complement Biomarker Panel, Complement Pathway Panel). This will require great coordination between the nephrology, hematology, and ICU team.

- Pradip, If our history, physical, and diagnostic investigation led us to HUS as our diagnosis what would be your general management of the framework?

- After careful attention to airway, breathing circulation and good basic PICU care, supportive therapy is the cornerstone of the treatment of HUS patients admitted to the PICU.

- Let’s organize our management model into key PICU management components: fluid and electrolyte management, blood pressure control, transfusion thresholds, plasma exchange and antimicrobial

- Fluid, Electrolytes and Nutrition:

- Early volume expansion especially prior to development of acute kidney injury has been shown to have also proven to lessen the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) as well as reduce central nervous system-associated complications.

- Once AKI develops, the intensivist will have to work with the nephrologist to provide dialysis. Typically at our institution this is done using CVVH although peritoneal dialysis can also be used.

- CVVH will help reduce volume overload, correct electrolytes, acidosis and allow provision of nutrition. We typically use citrate regional anticoagulation.

- Blood pressure control:

- Hypertension is common in HUS.

- Early use of titratable IV nicardipine especially for severe hypertension followed by transition to PO meds is recommended.

- Blood and platelet transfusion:

- Transfusion of pRBCs should be considered only in symptomatic children whose hemoglobin is < 7gm/dL.

- Platelet transfusion must be restricted to active bleeding or invasive surgical procedures.

- Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma also should be avoided unless there is active bleeding.

- You’re absolutely correct, FFP which contains clotting factors & complement mediators may actually fuel your inflammatory cascade. A discussion with blood bank/hematology may be required to see if there is a role for “dextran washed RBCs” which removes more than 95% of plasma from donor pRBCs.

- Rahul, is there a role for plasma exchange in these patients?

- Plasma exchange:

- No role for plasma exchange in STEC-HUS although it has been used in STEC-HUS with neurological involvement in adults (grade 3 recommendation of the American Society of Apheresis). There is no indication for IVIG, steroids, aspirin, heparin or anti-fibrinolytic agents either.

- Antibiotics: Antibiotics are contraindicated as they can cause HUS as well as favor release of Shiga Toxin, or provide selection pressure if the organism is not fully eliminated.

- Pradip are there immunomodulating agents we can give, especially if we are thinking atypical HUS?

- In atypical complement mediated HUS: Impairment of complement activity regulation leads to uncontrolled complement activation in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

- The use of humanized monoclonal antibody Eculizumab (trade name Soliris) is recommended. Eculizumab binds with complement protein C5 (preventing cleavage into C5a and C5b) and blocks activation of terminal complement pathway C5b-9. The drug works within an hour of administration and early use may help recovery of renal function. An initial induction dose is given in week 1, followed by maintenance dosing at week 2 and then every 2 weeks after that. Patients require prophylaxis against meningococcal/pneumococcal diseases by using a vaccine or antibiotics such as amoxicillin.

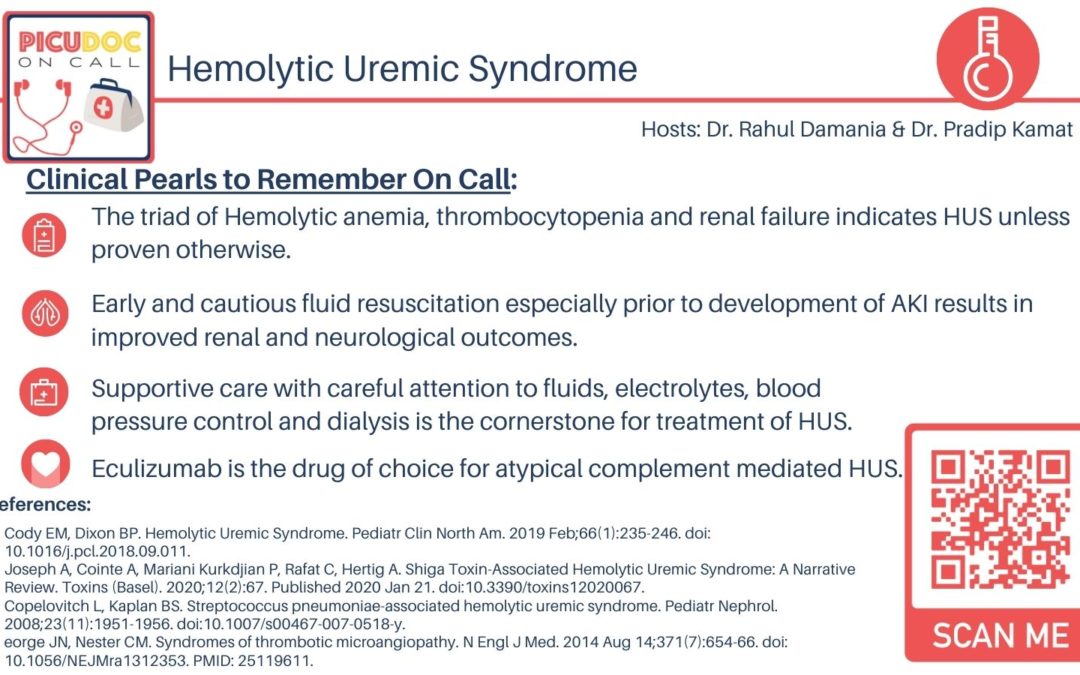

Lets summarize the Key objective take-aways from today’s episode:

- The triad of Hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and renal failure indicates HUS unless proven otherwise

- Early and cautious fluid resuscitation, especially prior to development of AKI, results in improved renal and neurological outcomes.

- Supportive care with Careful attention to fluids, electrolytes, blood pressure control and dialysis is the cornerstone for treatment of HUS

- Eculizumab is the drug of choice for atypical complement mediated HUS

This concludes our episode on Hemolytic uremic syndrome. We hope you found value in our short, case-based podcast. We welcome you to share your feedback, subscribe & place a review on our podcast! Please visit our website picudoconcall.org which showcases our episodes as well as our Doc on Call management cards. PICU Doc on Call is hosted by myself Pradip Kamat and my cohost Dr. Rahul Damania. Stay tuned for our next episode! Thank you!

- References:

- Cody EM, Dixon BP. Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2019 Feb;66(1):235-246. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.09.011

- Joseph A, Cointe A, Mariani Kurkdjian P, Rafat C, Hertig A. Shiga Toxin-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Toxins (Basel). 2020;12(2):67. Published 2020 Jan 21. doi:10.3390/toxins12020067

- Copelovitch L, Kaplan BS. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(11):1951-1956. doi:10.1007/s00467-007-0518-y

- George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014 Aug 14;371(7):654-66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312353. PMID: 25119611.