Welcome to PICU Doc On Call, A Podcast Dedicated to Current and Aspiring Intensivists.

I’m Pradip Kamat and I’m Rahul Damania and we are coming to you from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta – Emory University School of Medicine.

Welcome to our PICU Doc On Call Mini-Case series. In this episode, we present a 15 year old girl who is admitted for shock after returning from her recent travel to NIgeria.

Here’s the case:

13y F with no significant past medical history presents with 4 days of fever, headache, watery, non-bloody diarrhea, non-bloody, non-bilious emesis, decreased PO intake with worsening myalgias, fatigue, and weakness. She had traveled with her mother to Nigeria earlier this month and returned a week ago. Over the weekend mom consulted her pediatrician who prescribed an antiemetic without significant improvement of her symptoms. Once patient progressed to becoming light headed and weak, the mom decided to bring her to ED where she was found to be have tachycardia and hypotension. She required 3 L of crystalloid resuscitation was started an epinephrine continuous infusion and transferred to the PICU. Patient was found to have acute kidney injury with an elevated Cr, as well as a primarily direct hyperbilirubinemia and associated anemia and thrombocytopenia.

Her other history elements were notable for fever and difficulty breathing. Prior to traveling to Nigeria she did receive travel vaccinations and took mefloquine prophylaxis. She also had a negative COVID screen. While in Nigeria she denies exposure to animals, raw food intake, and only recalls that she may have had a few mosquito bites but this was well after returning from Nigeria until 7 days prior to presentation to the ED.

She presents to the PICU with hypotension, tachycardia at 160 bpm, tachypnea, and normal saturations. Her physical exam is notable for cool peripheral extremities, RUQ tenderness, and bilateral crackles.

She had no murmurs or gallops on her initial exam. Pertinently, she had no rash, lymphadenopathy or scleral icterus.

- This is a teenage girl who has fever and constitutional symptoms after returning from travel abroad

- She now presents with fluid refractory shock, tachycardia that is out of proportion to dehydration and signs of end-organ failure.

- Notable negatives include: No LNadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or a rash

- Synthesizing these symptoms together → we are thinking that this picture may be related to a contracted infection or inflammatory condition related to her travel.

- Let’s transition into some history and physical exam components of this case.

- What are key history features in this child who presents with fever and shock after a recent travel outside the US (Nigeria-West Africa)

- Diarrhea and emesis days before presentation

- High Fever with no rash

- Mental status is maintained although she did have an headache

- Light headed and weakness are symptoms suggestive of dehydration and even shock

- Physical exam findings of importance here include- patient presenting with tachycardia, signs of poor perfusion such as delayed cap refill, cool extremities, hypotension. It is unique that even though she has RUQ pain there is no jaundice.

2. Are there some red-flag symptoms or physical exam components which you could highlight in a

patient with the above history and recent travel.

- Weakness, light-headedness, shock, tachycardia, poor perfusion, fever and evidence of multi-organ dysfunction are suggestive of an acute and possibly life threatening infection acquired during travel. Given her travel to West Africa: I would be worried about falciparum malaria, dengue fever, typhoid fever, and cholera. Other diseases to be concerned about especially given her travel h/o include leptospirosis, chickungunya, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, African tick bite fever etc. I would be also concerned about bacterial sepsis with a source such as the kidney, bowel, or intrapelvic organs.

- To continue with our case, the patients labs were consistent with:

- Anemia 11/33, thrombocytopenia 12, and leukopenia WBC 4.55 with 92% segs. On her smear her RBC morphology was described as normal.

- Elevated BUN and creatinine with no acidemia

- Elevated liver enzymes (AST/ALT and Tbilirubin). Although her synthetic liver function was preserved

- Elevated lactate, a BNP of 309 and troponin of 11.5.

- Given her fever and travel history the ED team also sent a blood culture (large volume) and a thick and thin smears for malaria. In the PICU after consulting with ID service , we sent GI PCR, Dengue serology IgM and IgG) and NS-1 antigen.

- We also did an EKG, ECHO (given her tachycardia and shock).

- The lab personnel called to report that a malarial parasite was seen at 0.8% on the smear. The ID attending who examined the smear confirmed multiple ring forms in cells which goes along with Plasmodium falciparum, but unable to exclude different types of Malaria. A PCR for speciation of type of malaria was also sent.

OK to summarize, we have a:

- 13 yo female who presented with, fever, shock, and multi-organ dysfunction with a h/o recent travel. Given the findings of falciparum malaria on her blood smears, we confirm a diagnosis of falciparum malaria in this patients. Although her parasitemia level is < 5%, her clinical presentation of shock, AKI suggests she has severe malaria.

- Let’s start with a short multiple choice question:

- A patient with severe Falciparum malaria who presents in shock, AKI and a parasite level of 10%, and inability to keep PO medications due to emesis, which of the following in the initial drug of choice?

- A. Quinidine

- B. Artemesin

- C. Artensunate

- D. Doxycycline

- Correct answer is C. Artensunate given IV. As recommended by the CDC as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Red book. IV Quinidine is no longer available in the US.

- Artemesin can be used if patient can tolerate PO while awaiting IV Artensunate. Drugs like doxycycline are slow acting antimalarials that would not take effect until well after 24 hours and are not effective in severe malaria. Other PO medications which can be used include artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem™) because of its fast onset of action as well as atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone), quinine, and mefloquine. As for any malaria treatment, the interim regimen should not include the medication used for chemoprophylaxis if possible.

- As you think about our case, what would be your differential?

- Broadly speaking you want to think about other causes of fever, and shock with multiorgan dysfunction in a traveler returning to the US, I would think of

- Sepsis (pyelonephritis, pneumonia, ruptured appendicitis, ovarian abscess etc.): Negative blood culture

- Leptospirosis (no exposure to rodent or food contaminated with rodents urine or feces. No conjunctivitis, rash or jaundice)

- Typhoid fever (GI PCR would confirm)

- Dengue (no rash or muscle/joint or eye pain

- Chickungunya (no joint pain or rash, argues against this)

- Ebola (lack of conjunctivitis, DIC/hemorrhage)

- Food poisoning and hypovolemic shock (fever would be unlikely)

- Always think of SARS-COV-2 especially in this child who is not vaccinated. Her presentation with fever, GI symptoms and shock could be a manifestation of MIS-C. (SARS CoV-2 Ab negative)

- Rahul if a patient develops a fever or symptoms 21 days after travel to a foreign country certain disease such as dengue, rickettsial infections, Zika virus infection, and viral hemorrhagic fevers are unlikely, regardless of the traveler’s exposure history.

- Infectious causes may be further narrowed by pretravel vaccinations and chemoprophylaxis, although neither approach is 100% effective like our patient who did not take her mefloquine correctly. The incubation period (time to onset of malaria symptoms) in most cases ranges from as soon as 7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito to about 30 days and is shortest for P falciparum and longest for P malariae

- If you had to work up this patient with severe malaria what would be some of the lab investigations you would send:

- Fever in a returning traveler requires a good history and a physical examination. Besides a complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, CRP, Procal, blood Cx (large volume), UA/UCx and in a patient with shock and poor perfusion- I would send a lactate, get a chest radiograph, EKG and an echocardiograph.

- After consulting with infectious diseases: I would send thick and thin (to speciate type of parasite) blood films to test for malaria parasite. The thick film allows for concentration of the blood to find parasites that may be present at low density, whereas the thin film is most useful for species identification and determination of the density of red blood cells infected with parasites. If initial blood smears test negative for Plasmodium species but malaria remains a possibility, the smear should be repeated every 12 to 24 hours during a 72-hour period, ideally with at least 3 smears. Serologic testing (rapid diagnostic test or RDT) generally is not helpful. PCR is most useful to confirm species of malaria. If there is diarrhea and vomiting then a GI PCR and testing for SARS-COV-2 maybe useful. If there are respiratory symptoms respiratory viral panel which includes SARS-COV-2 must be performed. Serologic testing for dengue, chikungunya, leptospirosis and rickettsioses may be required. If there is fever with abdominal pain or tenderness- suspect acute cholangitis (stones, liver flukes), liver abscess (pyogenic or amoebic)-may need ultrasound, blood cultures or stool examination. Practitioners to keep in mind that the returning traveler may present with ruptured appendicitis, UTI/pyelonephritis, pancreatitis etc). These conditions need to be sought with appropriate lab and imaging.

To summarize – thick smears finds the parasites whereas thin is for species identification

- If our history, physical, and diagnostic investigation led us to severe malaria as our diagnosis what would be your general management of framework?

- Let me reiterate that a patient is said to have severe malaria if the patient’s parasite load is ≥ 5% or the patient has any of the following:

- Impaired consciousness, Seizures, Circulatory collapse/shock, Pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), Acidosis, Acute kidney injury, Abnormal bleeding or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), Jaundice (must be accompanied by at least one other sign) and Severe anemia (Hb <7 g/dL).

- Cerebral malaria, characterized by altered mental status and manifesting with a range of neurologic signs and symptoms, including generalized seizures, signs of increased intracranial pressure (confusion and progression to stupor or coma), and death

- Any patient with severe malaria requires admission to the PICU as there can be rapid decline in the patients clinical status. Initial management of airway, breathing followed by resuscitation with balanced intravenous fluids should be started. Frequent checks as well as correction of glucose and electrolyte imbalances is recommended as well as close monitoring of urine output.

- Rahul our patient had mild cardiomegaly on CXR, mildly depressed cardiac function (LV and RV) on echo and mild elevation of her BNP and troponin. Can you shed some light on myocardial depression in patients with severe malaria?

- Pradip-initially our patient presented in shock so a quick echo done at bedside revealed some mild-moderate cardiac dysfunction with no pericardial effusion. An EKG revealed diffuse ST segment elevation. Patient was on epinephrine and MIlrinone for her cardiac dysfunction. Her echo+ekg findings along with elevated biomarkers were strongly suggestive of malarial myocarditis. Mainstay of treatment consists of hemodynamic cardiac support and treatment of the underlying malarial infection. We saw gradual improvement of her cardiac function with malaria therapy. In fact a cardiac MRI done prior to discharge was completely normal.

A recent paper by Kotlyar et al in PCCM journal (2018; 19:179–185) reported on myocardial function and Injury by echocardiography and cardiac biomarkers in African Children with severe plasmodium falciparum malaria. The authors reported from their echocardiographic data that most children (96.2%) with severe P. falciparum malaria have normal EF despite some elevation of the cardiac biomarkers. Although there was evidence for myocardial injury (elevated cardiac troponin I), this did not correlate with cardiac dysfunction.

- Pradip Let’s go into specific elements of management, how would you treat severe malaria

- CDC malaria clinicians are on call 24/7 to provide advice to healthcare providers on the diagnosis and treatment of malaria and can be reached through the CDC Malaria Hotline

- For severe malaria: IV artensunate is the drug of choice . If patient is able to take PO, the patient should be treated with artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem™) because of its fast onset of action, or atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone). When IV artesunate arrives, immediately discontinue the oral medication and start parenteral treatment. Each dose of IV artesunate is 2.4 mg/kg. A dose of IV artesunate should be given at 0, 12, and 24 hours. Patients on treatment for severe malaria should have one set of blood smears (thick and thin smear) performed every 12–24 hours until a negative result (no Plasmodium parasites are detected) is reported. If, after the 3rd IV artesunate dose, the patient’s parasite density is >1%, IV artesunate treatment should be continued with the recommended dose once a day for a maximum of 7 days until parasite density is ≤1%. Doses given at 0, 12, and 24 hours count as 1 day, which means up to 6 additional days. Clinicians should proceed with full course of oral follow-on treatment as above as soon as parasite density ≤1% and the patient is able to tolerate oral medications.

- Intravenous artesunate is safe in infants, children, and pregnant women in the second and third trimesters. The only formal contraindication to IV artesunate treatment is known allergy to IV artemisinins.

- All persons treated for severe malaria with IV artesunate should be monitored weekly for up to four weeks after treatment initiation for evidence of hemolytic anemia.

- As for any malaria treatment, the regimen selection should not include the medication used for chemoprophylaxis.

- Previously, CDC recommended exchange transfusion be considered for certain severely ill persons. However, exchange transfusion has not been proven beneficial in an adequately powered randomized controlled trial. In 2013, CDC conducted an analysis of cases of severe malaria treated with exchange transfusion and was unable to demonstrate a survival benefit of the procedure. Considering this evidence, CDC no longer recommends the use of exchange transfusion as an adjunct procedure for the treatment of severe malaria.

This concludes our PICU Mini case Series Episode on Fever and shock in the PICU patient after recent travel . We hope you found value in our short, case-based podcast. We welcome you to share your feedback, subscribe & place a review on our podcast! Please visit our website picudoconcall.org which showcases our episodes as well as our Doc on Call management cards. PICU Doc on Call is hosted by myself Pradip Kamat and Dr. Rahul Damania. Stay tuned for our next episode! Thank you!

- More information can be found

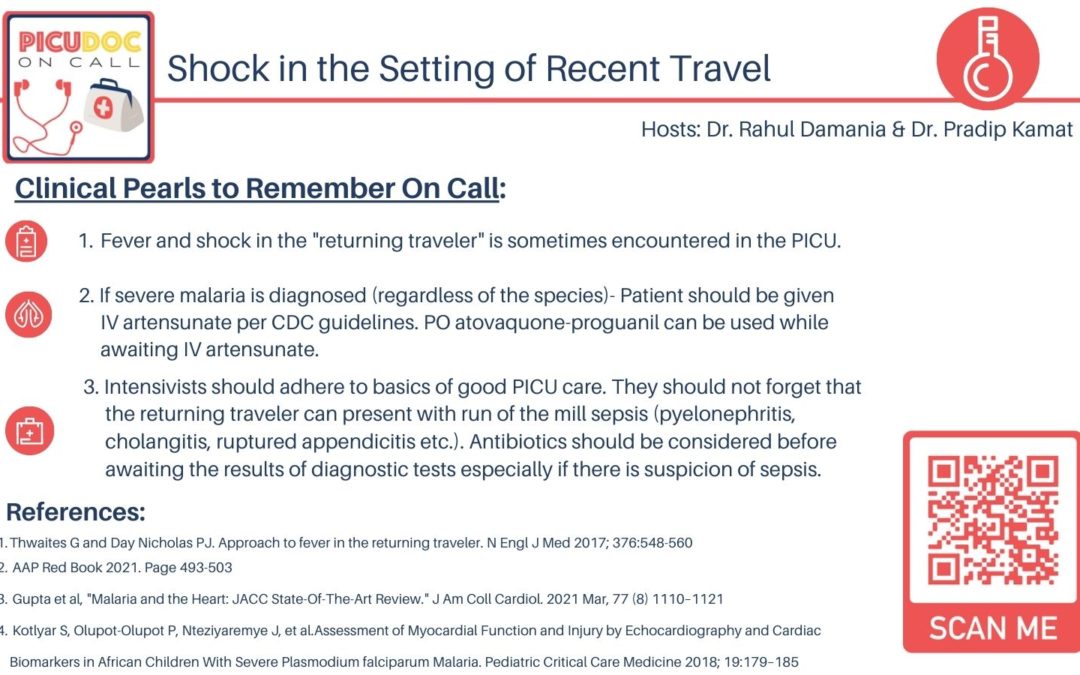

- Thwaites G and Day Nicholas PJ. Approach to fever in the returning traveler. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:548-560

- AAP Red Book 2021. Page 493-503

- Gupta et al, “Malaria and the Heart: JACC State-Of-The-Art Review.” J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Mar, 77 (8) 1110–1121,

- Kotlyar S, Olupot-Olupot P, Nteziyaremye J, et al.Assessment of Myocardial Function and Injury by Echocardiography and Cardiac Biomarkers in African Children With Severe Plasmodium falciparum Malaria. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2018; 19:179–185