Today’s episode is dedicated to the approach to the unstable neonate. Join us as we discuss the anatomic and physiological considerations for the neonate, initial investigations, and management framework on stabilizing a child.

We are delighted to be joined by Dr. Michael Wolf, Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine, and Associate Medical Director of the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. The CICU at Children’s is one of the highest volume pediatric heart centers in the nation. Dr. Wolf is also Chair of the “You Matter Program” at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, which addresses physician resilience and second victim syndrome in providers.

Show Highlights:

- Our case, symptoms, and diagnosis: A 4-day-old former full-term neonate delivered via C-section for non-reassuring fetal heart tones is to be discharged from the well-child nursery. On the day of discharge, the child is noted to have progressive tachypnea, tachycardia, and progressive acrocyanosis. The extremities are cool, and the child has delayed capillary refill. Pulse-oximetry is notable for a discordance between upper and lower extremity saturations. Femoral pulses are poorly palpable. Blood gas is significant for metabolic acidosis. The patient is rushed to the NICU, and the process to transfer the baby to a pediatric cardiac intensive care facility is initiated.

- Important considerations to keep in mind for the neonatal or infant population are according to the traditional Airway-Breathing-Circulation model:

- Airway–The infant airway is prone to dynamic obstruction due to a larger tongue and epiglottis, compliant soft tissues, and their obligatory nose breathing.

- Breathing–Differences in chest wall dynamics, oxygen metabolism, and respiratory musculature place the small infant at greater risk for respiratory failure than the older child.

- Cardiac–Considerations focus on key events in the transition from fetal to neonatal circulation, and include the initiation of prostaglandins and calcium administration to drive contractility..

- Shock categories to consider for the neonate include hypovolemic shock from hemorrhage, obstructive entities like severe pulmonary hypertension, and septic shock.

- Initial stabilization of the neonate includes the following lab testing and imaging: blood gas and glucose determination, basic electrolytes, vital signs and clinical exam data, and prostaglandin infusions to reestablish blood flow. The loop of intervention and reassessment is imperative as you acutely stabilize a child with neonatal shock!

- Other key diagnostics include four extremity blood pressure and low extremity pulses, pre- and post-ductal saturations, bedside echocardiography, and delving into the history with prenatal screening.

- The management framework focuses on prostaglandins and dosage protocols, the availability of intubation equipment, and the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).

- Besides congenital heart defects, other considerations for the unstable neonate are sepsis, infusions of ionotropes, cardiac catheterizations, and possible balloon valvuloplasty.

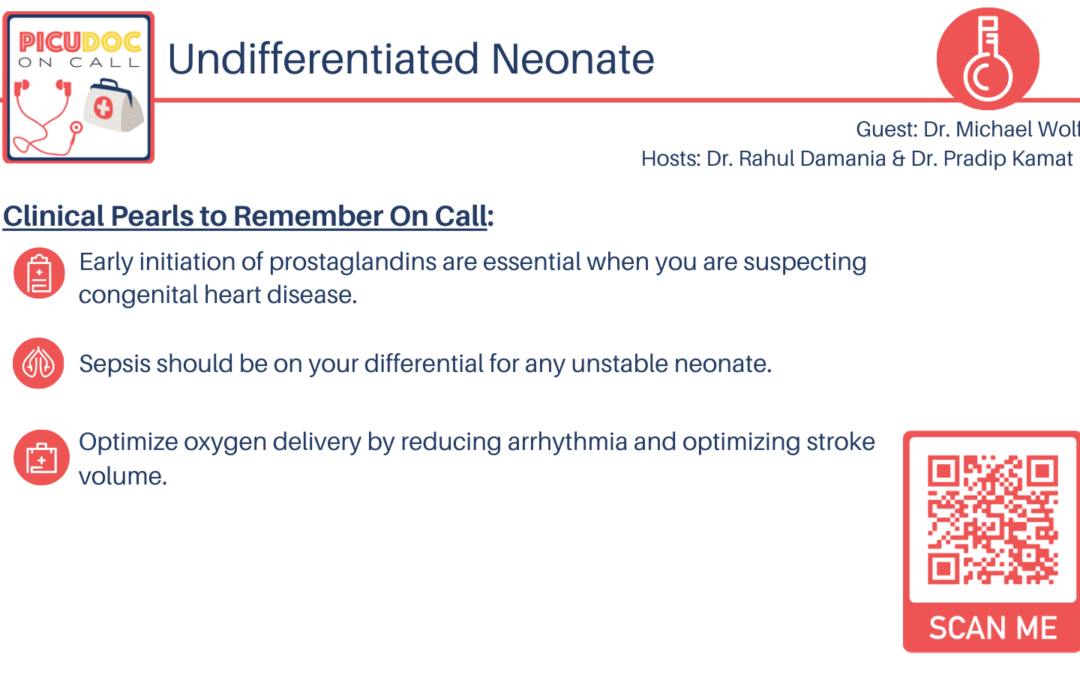

- Takeaway clinical pearls regarding the unstable neonate:

- Always think about prostaglandins when approaching the neonate with shock.

- Use a physical exam to check pulses and blood pressure.

- Remember that a focused, rapid, bedside echocardiogram can help diagnose shock.

- We hope you learned something from today’s discussion of the importance of a broad differential, key presentation features of congenital heart disease, and the importance of early PG initiation in the management of an unstable neonate.