Welcome to PICU Doc On Call, a podcast dedicated to current and aspiring intensivists. My name is Pradip Kamat

My name is Rahul Damania, a current 2nd year pediatric critical care fellow. We come to you from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and the Emory University School of Medicine Atlanta, GA

Today’s episode is dedicated to How to Read And Critically Review a Paper not only for the Journal club presentation at the fellows conferences but also for use in your clinical practice as a pediatric intensivist.

We are delighted to be joined by Jocelyn Grunwell, MD, PhD. Dr. Grunwell is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics-Pediatric Critical Critical Care at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, GA. She is a K-scholar with research interests in mitochondrial dysfunction in critical illness, the airway immune response in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome, and near-fatal asthma. She is on twitter @GrunwellJocelyn.

Rahul: Dr Grunwell welcome to picu doc on call. We are delighted to have you on our podcast today to discuss how to read & critically review a manuscript.

Grunwell: Thank you Rahul and Pradip for having me on PICU DOC on Call. I have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Q1. Rahul: Dr Grunwell: Why should a pediatric intensivist (whether in training or as a faculty) read journal articles?

Grunwell: There are several reasons you might want to read journal articles, and your reading should be tailored to your goals. For example, first, you may want to learn more about a clinical topic to understand how to diagnose, treat or manage a disease. 2nd you may want to find the best evidence for how to treat a patient. 3rd, you may want to learn about the basic biology or mechanisms of a disease. Finally, you may want to identify gaps in a particular field of research to develop a research plan and write a proposal to explore a new research area.

Q2: Dr Grunwell: Where do you find manuscripts relevant to intensivists?

First, I would like to suggest that the learners and faculty in pediatric critical care make a habit of reading at the very least the abstracts in various pediatric journals even if they don’t have the time to read an entire article. I generally go to Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Critical Care Medicine, Critical Care Explorations, Pediatrics, Journal of Pediatrics, NEJM, JAMA Pediatrics, and the family of American Thoracic Society journals on a weekly basis. You can set-up your account so that the table of contents of these journals will be emailed to you. There are apps available, such as ReadQxMD, where you can be alerted to new content of interest to you. You can sign up and follow the accounts of several journals of interest to you on Twitter. There is also a useful, free website sponsored by Dr. Hari Krishnan called picujournalwatch.com in which Dr Krishnan has journal articles well-organized. The website is constantly updated to show the latest manuscripts relevant to our field. You can keep your articles organized by topic in software such as EndNote. Also doing a search on PubMed, OVID etc. can also be helpful to find latest information on a topic. Talking to a medical library scientists is very useful to structure a systematic search for articles or to get a article from a journal that is not available at your institution.

Q3: Dr Grunwell can you define the term level of evidence?

Grunwell: the term level of evidence – or traditional hierarchy of evidence – refers to what degree that information can be trusted based on the study design.

The most common question is related to therapy or an intervention. Levels of therapy are typically represented as a pyramid with systematic reviews or meta-analyses positioned at the top of the pyramid followed by well-designed randomized control trials, and then observational studies. Observational studies include cohort studies or case-control studies. Case studies, laboratory-based studies with animal or in vitro models (aka: preclinical studies), and consensus or expert opinion lie at the bottom of the pyramid hierarchy. Based on this pyramid structure of evidence, the message is clear: Not all evidence and information is equivalent.

Q3. Pradip: Dr. Grunwell what is a critical appraisal of a manuscript and how does it help us?

Grunwell: Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers and it is used to judge the article’s trustworthiness, its value and relevance in a particular context. Critical appraisal helps you to systematically evaluate whether:

- The study addresses a CLEARLY FOCUSED QUESTION

- The study uses VALID METHODS to address this question

- The valid results of the study are IMPORTANT

- The VALID, IMPORTANT results are APPLICABLE to your patients or population

So the goal of learning critical appraisal helps you:

- identify the most relevant papers

- distinguish evidence from opinion, assumptions, misreporting, and beliefsP

- assess the validity of the study

- assess the usefulness and clinical applicability of the study

- recognize any potential for bias.

Q4. Dr Grunwell what are some of the key components of the appraisal process of a manuscript?

I generally ask 3 preliminary questions when I look at a paper:

- What was the research question and why was the study needed? ( After a brief background about the topic under study, the paper’s introduction should clearly state the research question and the hypothesis.)

- What was the research design? (For example, is this a primary or secondary study; If primary, then was it a laboratory experiment, clinical trial, survey, observational, or a case series study? If secondary, then was it a review or a clinical guideline, decision analyses, or economic analyses)?

- Was the research design appropriate to the question? It can be helpful to categorize the study into a therapeutic, diagnostic, prognostic, randomized control trial, qualitative, an epidemiologic/descriptive study, or a meta-analysis. There are evidence-based medicine worksheets that can help you structure a formal review and make sure you consider all aspects of the study. These worksheets can be found in many different languages at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at The University of Oxford in the United Kingdom under Critical Appraisal Tools. The web address will be in the show notes (https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/critical-appraisal-tools) The Evidence-Based Medicine Toolbox from Toronto, Canada also have critical appraisal worksheets and resources to learn evidence-based medicine. This link will also be available in the show notes? https://ebm-tools.knowledgetranslation.net/.

OK to summarize, understand the question and the study design and then assess whether the appropriate design was used to answer a central question!

Q5. Dr Grunwell what is a general framework of how we should approach a manuscript?

Dr Grunwell: In order to explain the structure of a scientific paper, I use the analogy of a story. Think about your favorite fairy tale: there is a beginning – where the scene is set and the characters are introduced; there is a middle – where the action happens, and there is an ending – where there is a lesson learned or a moral of the story. By analogy, every scientific paper has an introduction – where you set the background and importance of the question and introduce the subject matter – the who, the what, and the why of the study). The middle of the article is where the action happens – you explain how you did the study in the methods section and what happened (what you found) in the results section. Finally, the article has an ending where you discuss the results within a larger context of other studies by comparing and contrasting, noting similarities and explaining discrepancies to other work, and acknowledging limitations. Finally you make a conclusion based on your results – can you recommend this therapy or diagnostic study for your patients?.

I really like the story analogy as this really frames our next segment of how to systematically read a scientific paper.

Q6. Dr Grunwell: What is the first step in the critical appraisal of the scientific paper?

A good first step would be just to skim through an article (start with the abstract) to understand the aims, key data and conclusions. Early considerations as you are skimming through the manuscript)-

- Main question – Relevant? Interesting?

- Original topic – Address a gap? Clear & easy to read?

- Conclusions consistent with the evidence presented?

- Do the experiments/data address the main question?

- Is there a disagreement with current consensus & is this disagreement justified by the data gathered?

- Do the Tables & Figures tell the story/add to the paper?

This is a bird’s eye view to get yourself oriented.

Dr. Grunwell, in general, how does the introduction help you as you critically appraise a manuscript?

Grunwell: When we look at the introduction we can formulate the problem

Define who the question is about? (how would I describe a group of patients similar to this one)

Define which maneuver you are considering in this patient or population and if necessary, a comparison maneuver: (drug treatment vs. standard therapy or placebo)

Define the outcome: Reduced mortality, length of stay, better quality of life cost savings, etc.

Q7 Pradip: As you read further after your broad overview how do you identify areas for improvement or major flaws in study design?

Dr Grunwell: I would encourage listeners to closely look at Tables, figures and images— What story are these data telling you? Can you recreate the story from the data presented WITHOUT reading a single word of the text? You should be able to follow the experimental argument and draw conclusions based solely on the evidence presented in the tables and figures.

Some things to watch for:

Are the authors drawing a conclusion that is contradicted by the author’s own statistical or qualitative evidence.

Are they using a discredited or flawed method?

- how are they sampling a population, do they have appropriate controls, how precise are their measurements, was the analysis conducted in a systematic manner?

- Are they asking a valid question?

-Are the authors ignoring a process that is known to have a strong influence on the area under study?

Asking questions which correlate to the author’s point of view is essential.

Correct, using this process it is important to summarize the research question by:

- Stating the main question addressed

- and Summarizing the goals or objectives.

- This helps to conceptualize the research, and allows focus on the successful aspects of the paper.

Transitioning to the methods section of a paper, Do Grunwell how do we assess the quality of the methods used in a study?

I guess the real question is whether the study in question is original and what does the new research add to the scientific literature? For example, is this a continuation of a large study or field of research.Does it address previous methodological shortcomings? Will numerical results add significantly to a meta-analysis?

Is the study population different?

Is the clinical issue important enough, or does there exist sufficient doubt in key-decision makers, to make new evidence ‘politically’ desirable?

Dr Grunwell as we assess the methods section how do we narrow in on the population of interest and specifically relate the methodology and paper to our patient cohort whom we serve clinically?

This is a great question. I would think about whether the patients

- Are the subjects more, or less, ill than who you see?

- Are the subjects of a different ethnicity, live a different lifestyle, from your own patients?

- Did the subjects receive more, or different, attention during the study that you can give your patients?

- Unlike most patients you care for, did the subjects have nothing wrong with them apart from the condition being studied?

- Did the subjects have potentially confounding exposures similar to your patients?

To summarize a central theme of our episode thus far is to read a paper with a perspective on how this applies to your setting – in our case it is critically ill children

Lets transition and talk about the layers of bias which may be present in the results or even discussion portion of the manuscript, Dr Grunwell can you highlight the sources of bias in a study?

Bias occurs when there is a systematic difference between the results from a study and the true state of affairs. Bias is often introduced when a study is being designed, but can be introduced at any stage. Appropriate statistical methods can reduce the effect of bias, but may not eliminate it. Increasing the sample size does not reduce bias.

We need to look at the treatment group and control group very closely to make sure both are treated equally.

Selection bias: can result from incomplete randomization. So patients included in the study are not representative of the population which you intended to analyze.

Performance bias can result from systematic differences in care received by the intervention and control groups because either the participant or the researcher know what group they were assigned – so there are differences in care received other than the intervention being compared

Exclusion bias refers to systematic differences in withdrawal or participants from a study arm. For example, there may be more withdrawals from the intervention compared to the placebo arm of a trial due to side effects; alternatively, there may be more withdrawals from the placebo arm of the trial compared to the intervention arm due to lack of improvement in clinical condition.

Detection bias is the systematic differences in outcome assessment between groups. Blinding (or masking) of outcome assessors may reduce the risk that knowledge of which intervention was received, rather than the intervention itself, affects outcome measurement.

Alright listeners lets summarize the various types of bias — selection is due to incomplete randomization, performance bias involves a lack of blinding, exclusion bias refers to the element of attrition, and detection bias refers to the impact the intervention has with respects to the control.

Dr Grunwell what are the preliminary statistical questions which need to be addressed in a manuscript?

Grunwell: Three statistical questions should be addressed:

First, there should be a sample size calculation to determine the power to detect a true difference between groups

–To calculate a sample size, there needs to be a defined amount of difference between 2 groups that is a clinically significant effect

–You will need to know the Mean and Standard deviation (or variance) of the principal outcome variable

Second, the study must be continued for long enough for the effect to be reflected in the primary outcome.

Third, the completeness of follow-up should be high. For example, < 70% follow-up may be sub-optimal. You can make an assessment of completeness by looking at the rate of withdrawal from the study (some reasons for low completeness include suspected adverse reaction, loss of motivation, loss to follow-up (moving from study area), or death).

Dr Grunwell lets conclude our podcast by going into how do you evaluate the Results and Discussion section of a manuscript?

The results should tell us what was discovered or confirmed. I make sure to see if it tells a coherent story. The authors should describe in simple terms what the data show and refer to statistical analyses such as significance and goodness of fit. Its should evaluate observed trends.

Explains significance of results to a wider understanding. Outcome should be a critical analysis of the data collected.

How do you look at the conclusion of a study?

The conclusion should basically reflect upon whether or not the aims are achieved. Conclusion should not have surprises in them and should be evidence-based. It typically is short and relates directly to the question and outcome.

Dr Grunwell this was a wonderful summary and discussion today — what our resources our listeners can utilize to improve their understanding about research methodology:

How to read a paper by Trisha Greenhalgh

Users’ Guide to medical literature by Gordon Guyatt

I also would recommend writing science by Joshua Schimel.

I always give my fellows a paper by my undergraduate research mentor, Professor George M. Whitesides titled the “Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper” in the journal Advanced Materials.

I recommend that PCCM fellows keep reading papers in PCCM and CCM journal – at the very least peruse through the abstracts especially when they are busy on-service, etc. Structured and interactive journal clubs can help practice critical appraisal skills.

A community approach is definitely essential in staying current on new research?

Dr. Grunwell we appreciate your insights on today’s podcast, as we wrap up, would you mind highlighting your personal pearls with respect to critical appraisal of manuscript ?

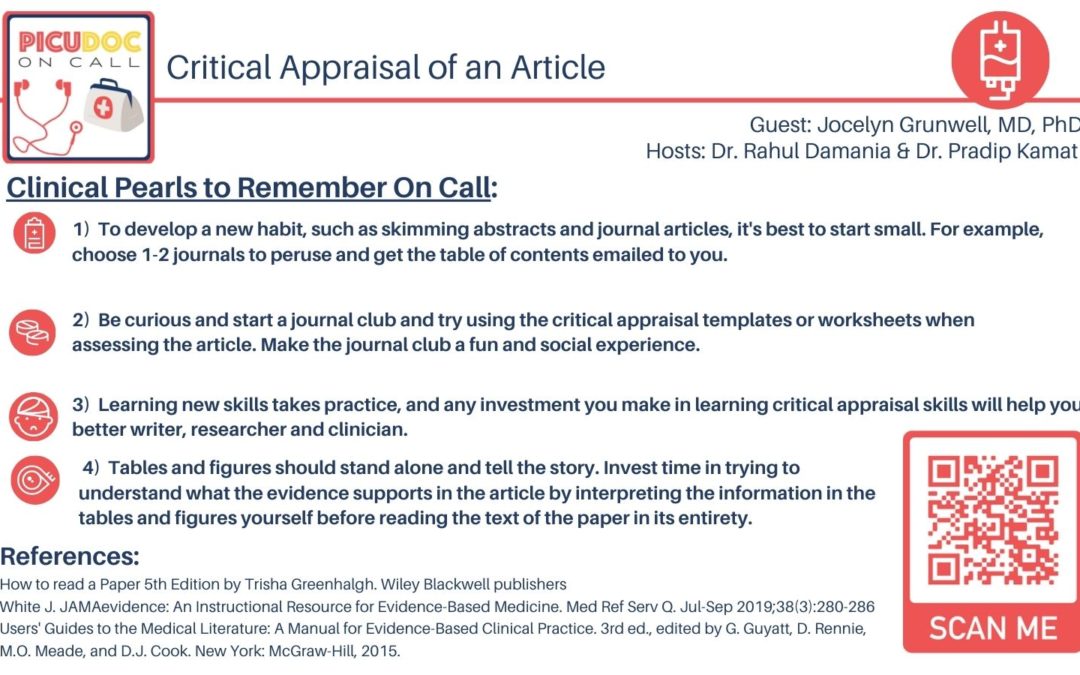

- To develop a new habit, such as skimming abstracts and journal articles, its best to start small. For example, choose 1-2 journals to peruse and get the table of contents emailed to you.

- Be curious and start a journal club and try using the critical appraisal templates or worksheets when assessing the article. Make the journal club a fun and social experience.

- Learning new skills takes practice, and any investment you make in learning critical appraisal skills will help you become a better writer, researcher and clinician.

- Tables and figures should stand alone and tell the story. Invest time in trying to understand what the evidence supports in the article by interpreting the information in the tables and figures yourself before reading the text of the paper in its entirety.

We went through a systematic process on how to collect, organize, synthesize & apply journal articles from manuscript to bedside! Having close collaboration with your medical librarian is essential along with a curiosity to learn is essential to optimize your evidence based knowledge and stay up to date on the literature

This concludes our episode today on how to read a paper. We thank Dr Jocelyn Grunwell for her expertise on this topic. We hope you found value in this short podcast. We welcome you to share your feedback & place a review on our podcast. PICU Doc on Call is co-hosted by me Pradip Kamat and myself Dr. Rahul Damania.

Stay tuned for our next episode! Thank you

References:

How to read a Paper 5th Edition by Trisha Greenhalgh. Wiley Blackwell publishers

White J. JAMAevidence: An Instructional Resource for Evidence-Based Medicine. Med Ref Serv Q. Jul-Sep 2019;38(3):280-286

Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. 3rd ed., edited by G. Guyatt, D. Rennie, M.O. Meade, and D.J. Cook. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2015.