Today’s episode is dedicated to venous/arterial thrombi, also known as catheter directed thrombolysis.

We are delighted to be joined by Dr. Anne E. Gill, Assistant Professor of Radiology and Imaging Sciences at Emory University School of Medicine. She is a pediatric interventional radiologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Her areas of expertise include pediatric thromboembolic disease, vascular malformations, enteric feeding tube access, and interventional oncology. Dr. Gill is on Twitter @AnneGillMD.

Show Highlights:

- Our case, symptoms, and diagnosis: A 17-year old girl with antithrombin III deficiency presented with bilateral leg pain to an outside ED. Duplex ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities revealed extensive acute bilateral deep vein thrombosis. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed an extensive occlusive clot in the inferior vena cava involving the infrarenal and suprarenal IVC. She was transferred to our hospital and admitted to the ICU for thrombolysis and initiation of catheter-directed TPA infusion. In interventional radiology, an IVC filter was placed in the suprarenal IVC; additionally, the venogram in IR showed complete thrombosis of the right upper femoral, external iliac, common iliac, and IVC, with collateral veins in the right lower extremity draining into the thrombosed upper femoral vein. Interventional radiology performed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis and balloon angioplasty of right external iliac, common iliac, and IVC and placed infusion catheter to drip tPA from right femoral vein to the IVC filter. The patient was also placed on continuous heparin drip for systemic anticoagulation management. Morphine and Dexmedetomidine were used for pain management.

- The overall prevalence of systemic venous occlusion in children is difficult to ascertain due to their asymptomatic quality.

- Congenital SVOs in children can be due to developmental hypoplasia or agenesis of major conducting veins; they can happen in utero or manifest as neonatal thrombosis.

- Acquired causes of SVOs can include catheter acquired obstruction, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, mechanical obstruction, and trauma.

- A careful history is necessary to determine whether the occlusion was a congenital or acquired SVO.

- This is challenging because symptoms of venous obstruction in children may not present until later in life.

- This distinction is important as it affects the procedures that can be done.

- Better outcomes are possible if a native pathway is present, even if it’s diminished from chronic obstruction and scarring.

- Clinical presentations of systemic venous occlusions in children include head and neck swelling coupled with shortness of breath. In patients with acute DVT, venous congestion can manifest as prolonged capillary refill, coolness of extremities, and bluish discoloration to frank venous ischemia with loss of pulses.

- Chronic DVT in extremities can present with a sense of heaviness, aching pain, and fatigue with activity; these symptoms are collectively described as post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Remember that obstruction to flow can compromise oxygen delivery!

- Common causes of venous occlusions are mal-positioned or wrongly sized central venous catheters, May-Turner syndrome, and long-standing central venous access lines in dialysis patients.

- CDT is not recommended for DVTs below the inguinal ligament, based on the ATTRACT trial in 2017 that showed that CDT is most beneficial in veins above the inguinal ligament.

- Contraindications for CDT in children include allergy to tPA, active bleeding, surgery within the last 14 days, any invasive procedures in the last three days, recent seizures, recent trauma, or coagulopathy which can’t be easily corrected. Caution is needed with premature infants and those with HTN or other risk factors for bleeding.

- Diagnostics needed prior to consulting on a patient with venous occlusion include Doppler US, CT or MRI to visualize central vessels, cone-beam CT (CBCT), and hematology consult.

- General principles of venous recanalization for acute venous occlusion:

- Acute venous occlusions are typically related to acute thromboembolism.

- Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is a valuable tool.

- CDT with a catheter dripping tPA overnight.

- Balloon angioplasty followed by systemic anticoagulation.

- Treatment options for chronic venous occlusions range from endovascular angioplasty and stenting to surgical bypass grafts or prosthetic graft reconstruction. Endovascular techniques are more widely accepted in pediatrics.

- Post-procedure patients in the PICU should have neurological monitoring and pain management, along with careful monitoring of the heparin infusion and tPA management. Worsening conditions may point to surgical interventions.

- Dr. Gill explains the protocol developed for heparin and tPA dosage and monitoring.

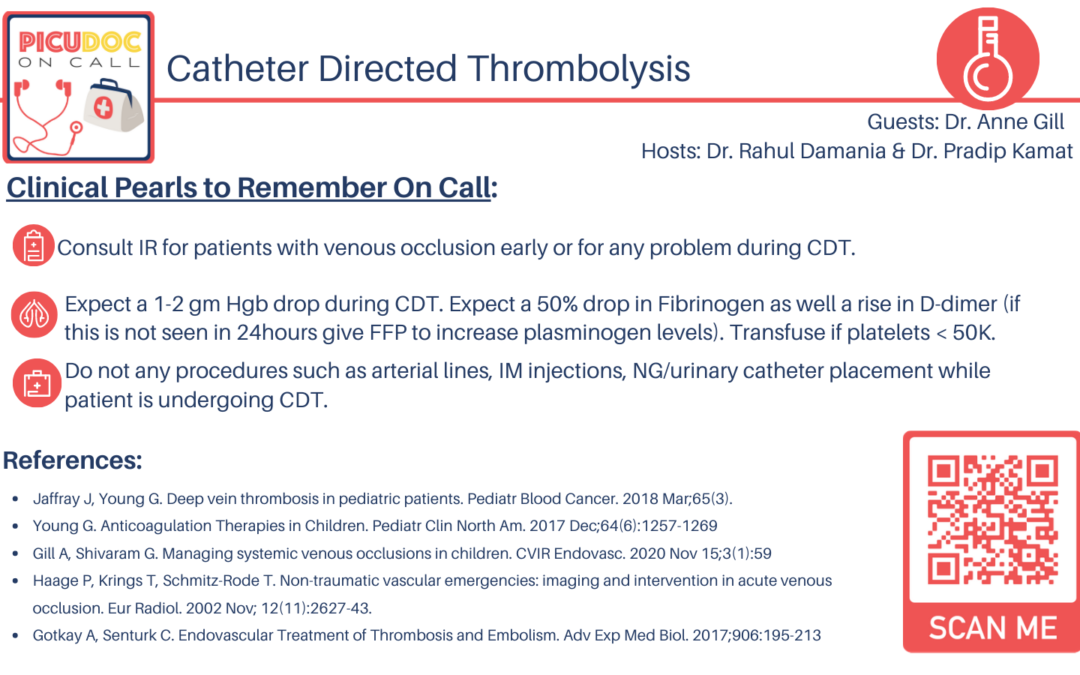

- Precautions needed by the PICU doctor for patients getting tPA and heparin include no arterial sticks, intramuscular injections, rectal temperatures, catheters, NSAIDs, or other platelet drugs. The key is a collaborative approach between interventional radiology, anesthesia, and hematology.

- Once the IR physician is satisfied with clot removal and blood flow in the previously occluded vessel, a decision is made to stop the tPA infusion.

- IR also provides other services like chest tube, PICC line, and GT placements, lumbar punctures, biopsies of liver/kidneys, and thermal ablation of solid tumors or painful bony metastases.

- Takeaway clinical pearls include the collaborative team of anesthesia, hematology, PICU, and IR for optimal outcomes. IR should be called early and often. Labs should be followed closely, especially Fibrinogen, platelets, and hemoglobin/hematocrit.